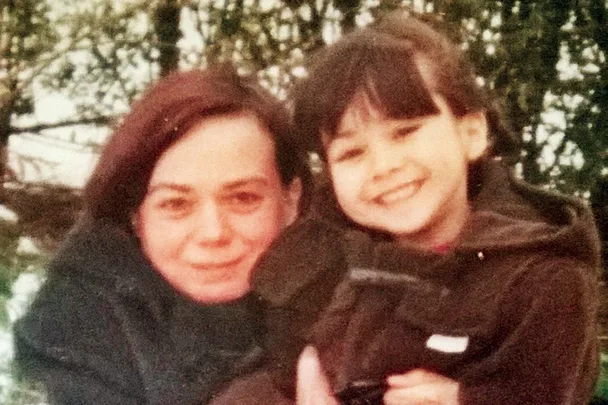

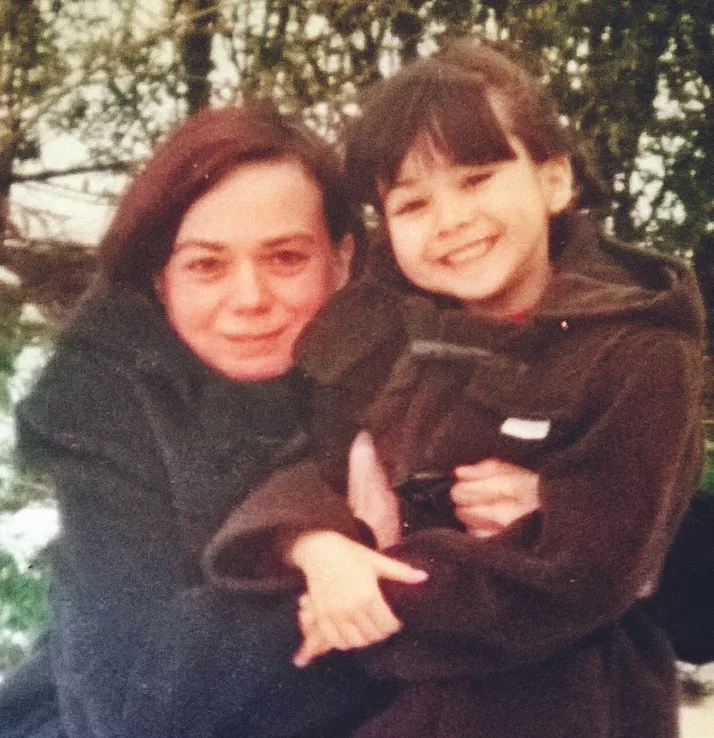

There is perhaps no greater grief than losing a child, and for Rosie Ayliffe that unimaginable loss became a reality when her 20-year-old daughter was fatally wounded in a Queensland backpacker hostel in 2016. Mia Ayliffe-Chung was on a gap year from the U.K., attempting to complete her 88 days of farm work—a requirement for a second-year working visa in Australia—when her roommate at Homes Hill Hostel in Townsville, armed with a knife, dragged her from her bed onto a nearby balcony and fatally stabbed her.

Following the death of her daughter, Rosie travelled to Australia where she heard stories of the terrible, exploitative treatment of young workers, ones exactly like Mia, including reports of widespread sexual and financial exploitation, which would later spark a years-long campaign to make sure no other parent would lose a child this way.

Now, pouring her grief into a new book, ‘Far From Home’, Rosie tells her story for the first time, revealing her fight for justice and providing an account of loss and survival in her own words.

Below, an excerpt from Rosie Ayliffe’s new book, Far From Home.

Mia’s Death

Nothing prepares you for news as calamitous as that we received on the evening of 23 August 2016. When the two police officers told us that Mia had been fatally wounded we were given very few details. But I remember feeling a sense of deja vu, almost as if I’d known this was going to happen.

The policemen informed Stewart and me that they could give us no more information than the basic fact of her death, and we were told we needed to call the Foreign and Commonwealth Office on a number they provided us. This seemed like a strange procedure, but we were in no position to ask questions. So I called immediately, and the phone was answered just as quickly by a confident, well-modulated voice. He informed me that Mia had received her fatal wound at the hands of a young man at the hostel, a French national called Smail Ayad. He told me that there was no doubt about this as it had been captured on CCTV footage. He told me that Ayad had been heard by other backpackers to shout ‘Allahu Akbar’ as he killed Mia, and that this was therefore being treated as a possible terrorist attack. He also informed me that another man called Tom Jackson had tried to save her life, and his life was now hanging in the balance. None of it made sense; my brain just refused to believe it was true.

The policemen sitting in my living room were obviously aware of this information already. They looked devastated on our behalf; I thought they had really drawn the short straw to be delivering this news from a police station as regional as ours, where more frequent crimes were badger baiting and the occasional incident of shoplifting. As they left they assured us that Howard, Mia’s father, was receiving a visit from the police simultaneously, so I didn’t need to speak to anyone until the following day.

Since then, I have been asked over and over how I felt on receiving that news. The absolute truth is I felt nothing. It was like I disassociated from my emotions, as if I were a bad actor in a movie I didn’t want any part of. I’ve learnt now about coping strategies and grief, about how the mind goes into denial, but at that point I was watching myself and wondering what was wrong with me.

I decided to call Home Hill Backpackers to try to find out more about the incident, feeling only compassion for the poor people who’d had to live through this incident on their premises. Apart from what I’d found out about the hostel online, I really knew very little about the place and I didn’t want to jump to any conclusions. However, even in a time of such high emotion, I found it strange that the person on the end of the phone was at pains to tell me what a lovely man Smail Ayad, Mia’s killer, had been. She said the attack had come out of the blue. I had just asked for information, and was certainly not looking to lay blame. In fact, my first thought had been that this could have happened anywhere so this seemed odd to me.

Stewart decided to take a day off work and stay with me the following day, which was a huge relief. I managed to persuade him to take himself up to bed once the policemen had left, though, as I felt I needed to be alone and work through my emotions. We’d asked the police if there was likely to be any press interest in the story, and they said yes, probably, because it was being investigated as a terrorist attack. I figured the local paper and BBC Central, our local TV station, would arrive on the doorstep, and so I tried—to no avail—to get Mia’s Facebook profile closed down. I suspected it would be pillaged for photos. Before she left the UK this wouldn’t have been a problem as she was careful about what she put on Facebook, but the youth culture on the Gold Coast is very different to that of a small-town environment, and there were many photos of Mia in her night- club outfit and in beachwear. I hadn’t tried to control this when she was enjoying her life, as the last thing I wanted was for her to feel I was being judgemental. She was a beautiful girl, and how she chose to dress was her business. But that night I was afraid she could be exploited for her looks in a world where people can so easily be commodified—to some extent she could still be naive and vulnerable, despite her adult appearance—and right now I didn’t want the press using those photos.

The first person I informed of Mia’s death was her ex-boyfriend, Elliot, who I saw was still online around midnight. I messaged him to tell him what had happened because I didn’t want him to find out from the press. Mia had been involved with him before she went to Australia, and I’d hoped it might pick up again on her return. Elliot was a sensitive, talented musician, who was well travelled and had a good work ethic, and I knew he adored Mia. He was clearly devastated by the news. Later he told me that he had been about to log off and turn in when I messaged him, but he was glad he had heard the news from me rather than from the media. It also meant he could approach me to talk about his grief later, and this formed a bond between us which helped us both through the coming weeks and months.

By about 3 am UK time, the news was breaking in Australia. This became my first of many long vigils spent conversing with people on the other side of the world at what were strange hours for me in my quiet corner of Derbyshire. I spoke to two of Mia’s girlfriends from the club in Surfers Paradise, Jesse Tawhi and Jordyn. They were both in shock, and I was aware of how hard it was for them to lose someone they had become so close to. They were expecting Mia to return in a few months, and had made space in their lives to receive her. Now that space was full of grief. I did what I could from such a distance to help them process their emotions, but I felt inadequate, and I really just wanted to hug them both.

I remember stepping outside to greet a pink-tinged, serene morning—it must have been about 6 am. I was in a dreamlike state from shock and sleeplessness, and my legs seemed to buckle under me. Nothing seemed to function properly, it was as if I’d been crippled by grief in the space of eight hours.

A little later, when I felt a bit more myself again, I took a coffee up to Stewart and as I opened the curtains I noticed people gathered out the front of the house, with more further down the road next to a van with what looked like recording equipment in their hands. I recognised the logo of ITV, one of our major independent TV channels, and groaned, sweeping the curtains closed as I did so. What looked like a large posse of press had arrived and it wasn’t yet 8 am.

I needed to think this through, and fast. News would be out in the UK that morning, if it wasn’t already, and I needed to let people know before that happened. I wrote a long post on social media for friends and family, knowing that word would spread around our small town in no time. I asked people not to speak to the press. At that stage, nobody really knew whether it was a terrorist attack or not, but it didn’t appear that way to me, and I didn’t want Mia’s death to be used to fuel any racist or anti-Islamic narrative. She would have felt completely let down by that.

Not everyone would be on social media at that time in the morning, of course. I learnt later that my dear friend Rachel, Mia’s godmother, who had travelled with us to Turkey on our first trip, heard the news on her car radio as she was driving and narrowly missed crashing into another vehicle as she was blinded by tears. Luckily she had managed to pull over before she broke down into a sobbing fit.

The Wiltshires, the family who lived on the hill farm above our town and whose kids Mia had minded for eight years, were on holiday in Portugal with Ned’s brother, Tom. The whole family were apparently sitting around in the living room when Tom opened his laptop and saw a picture of Mia and an article about her death. He cried out in shock, and his wife Paula ran over to read the article. Paula broke down at that point, and poor Jo, the beautiful mother who had been a huge influence on both me and Mia, had to cope with this terrible moment. She was faced with her children’s grief, her own emotions, Paula’s reaction, and all on top of recent news that her own mother had just had a stroke.

What followed back in Derbyshire was the most surreal day of my life. The police liaison officers arrived first. They were very sensitive, but they told Stewart and me they were learning that Mia had died in a horrific manner. This was tough to hear. They didn’t give details, but they did say they were convinced she wouldn’t have felt pain because of the incredible amount of adrenaline that would have been coursing through her body in the moments running up to her death. They told us that Ayad was a French national of Libyan descent, and that we should take information from them rather than the press. They also asked me to contact their press officer when I was ready to talk to the public.

After the police left, the street started to fill up even more with vehicles, and I realised I was going through one of those nightmare scenarios you think are the preserve of others, never you. The phone rang, and journalist after journalist found ways throughout the day to ask for interviews—there was no way I was entering into a dialogue with a single one of them that day. Family members were starting to learn of what had happened, and I took calls from my brother Mark, a devastated cousin Henry in Singapore, and my two sisters, Ruth and Jacqui. Thankfully, my father hadn’t lived to hear the news about the loss of his first and favourite grandchild, and Mum’s Alzheimer’s was at such a point that she had no comprehension of what had happened. However, I felt keenly the absence of my parents at a time when I desperately needed people to lean on.

One news reporter called to ask for an interview and a photo of Mia. I refused, and she said, ‘If you give us an interview, you can say it in your own words. Otherwise, we’ll write what we want to write, and use whichever pictures we want as well.’ Well, that was it as far as I was concerned; there was no way I was giving in to emotional blackmail, even when I was in such a vulnerable state.

Two local friends had offered to come over, and one of them happened to own a Subaru with blacked-out windows. I gave them both strict instructions not to speak to the press and persuaded them to park the car in a neighbouring carwash. Instead of going out through the front entrance of our house, we went to the end of our garden and with some difficulty managed to climb over the fence to meet my friends.

I needed to stave off the glare of publicity for a while until I’d collected my thoughts. I felt like quarry chased by a pack of hounds, but when we made it to the safety of the Subaru I was glad that we’d outwitted them. Not only had I not asked for this intrusion which felt totally inappropriate, but also, with my world spinning into a new orbit, I felt a strong need to take control of at least this little part of it.

From there we headed downhill in the car to our local pub, The Boat Inn, in Cromford. Everyone we encountered there had heard by then, and the family who owned the pub were struggling with the news themselves as they’d been close to Mia. There were many hugs and tears.

While at the pub, I took a second call from my brother Mark who said that my nieces were being harassed by the press at their respective university campus and school, so he asked me to make a statement. I knew I was in no fit state to do this, so I asked others to contribute their ideas and we cobbled together something which I gave to Stewart, who headed back up to the house with it.

I thought Stewart would be able to pass the piece of paper with our statement on it to the journalists and then disappear, but I’d forgotten that the TV cameras were there, and he had to try to read it out. He was in a state of deep grief and near exhaustion, and consequently, he sobbed through the entire rendition. If anything demonstrated the sheer horror of our day, it was his delivery. I remembered afterwards that I’d promised to make this statement through the police liaison officers, and they weren’t pleased that we’d circumvented them, but that was the least of my problems.

My view now is that the press should unilaterally allow those who are grieving a 24-hour moratorium to collect their thoughts and compose themselves. One’s dignity is so important after suffering a loss of this magnitude.

Later that day my sister Ruth arrived. She was upset as she’d been close to Mia. We talked through the facts of her death, and I told her that the only way I could cope was to think of Mia’s death as fated. Although she was a Christian, she disagreed with me on that front. She thought that Mia’s death had been avoidable.

All the time I was wondering why I still felt nothing. I hadn’t cried, I felt no grief. And yet my only daughter, my darling girl, my whole reason for being for the last twenty-one years since her conception, had gone.

That evening I started to recognise that I was in denial, as when I opened up the laptop, my first instinct was to look for a message from Mia. I realised I just hadn’t accepted her death. I could still hear her laugh, the one that gurgled up from her belly and spilled out like a rush of bubbles. I even knew what her reaction would be in such a situation. She would have been outside, with a tray of coffee mugs, courting the press, making jokes, and enjoying the limelight. I imagined her penning a statement, eulogising herself into a saint and adding in some sly swipes about my poor parenting! It wasn’t that I didn’t know she was dead, or that I didn’t know she wouldn’t come home, but it was a truth of such earth-shattering magnitude that I couldn’t accept it. In my heart of hearts, she was still out there, and this nightmare was a trial run for reality. My daughter wasn’t dead, I could save her, surely, through sheer willpower. The truth took a very long time to sink in, but at that stage I was protected by my hubris, or optimism, or denial. Call it what you will, I just wouldn’t accept the loss of Mia as the truth.

This is an excerpt from ‘Far From Home’ by Rosie Ayliffe, available now.